Secrets Of The Global Brain

These two words, supply and demand, seem very simple. They are known and supposedly understood by virtually anybody. They are ubiquitous, and if you know the words, but are a bit sketchy on the concepts, then you will fully understand them by the end of this post. Despite their simplicity, their understanding allows a virtual x-ray vision into the hive mind of society.

Not Economics

It’s a mistake to think of these as simple economic terms. When they are used, it’s common to say something like, “Duh, supply and demand, economics 101,” but in reality they have little to do with economics and everything to do with human nature. Another reason to read this post carefully. Once you understand the true nature of supply and demand, human behavior will be less of a mystery.

Should vs. Is

One idea we need get out of the way. There is the way people behave, and there is the way that we think people should behave. If you can’t understand the difference, this makes understanding human behavior much more difficult than it needs to be. If we look out into the world, and we decide people are not doing what we think they should be doing, then that means they are doing something else.

And unless we eliminate any should ideas from our thinking, we will be hopelessly confused by a kajillion variables. Why? Because every single human will have a slightly different idea about what all of the other humans on earth should be doing. So if we pretend we are talking about economics, or human behavior, what we are really doing is arguing about who’s got the best idea about what other people should be doing, that they aren’t actually doing.

And if we happen to agree on what all those other people should be doing (which they aren’t) then we will argue on the best way to make them do what we think they should do.

According To Whom?

A very handy question from NLP’s Meta Model whenever we hear a “should” based statement is to ask, “According to whom?” Or “What happens if they don’t?” Meaning if you and I were hanging out in your neighborhood bar, and you said, “Man, people shouldn’t be so loud at night.” What would you say to either of these questions:

According To Whom?

What Happens If They Don’t (be quieter at night)?

These questions are meant to make the should question seem more like an opinion. Many people spit out should statements as if they are objective facts. But in order to understand why should questions are really opinions, we need to understand something about human incentives.

What Are Incentives?

We do things to get more good stuff, or get less bad stuff. Those two reasons, and those two reasons alone, guide our every action. Either to improve or increase comfort, or to decrease or minimize discomfort. So let’s imagine our hypothetical loud neighbor. Does he stop in the middle of being loud, and wonder, “Gee, I’ll bet there are other people in the world who think I shouldn’t be loud, so I’d better stop”? Probably not.

Now, if his neighbor came over and bashed on his door every time he was loud, and it worked, does this mean he is now doing what he “should” be doing? Nope. It means now there are other incentives.

Before, when he was being loud, there were no negative repercussions. But now, every time he starts to become loud, he is worried his neighbor is going to come crashing through his door. This act (of bashing on his door whenever he is loud) has created a new incentive in his world. There are no shoulds in this equation.

People Do What People Do

So, let’s assume that people act because of the incentives. Sure, some of those incentives may be presented by people who believe they shouldn’t be doing what they are doing (or should be doing something they aren’t) but the real reason they have changed their behavior are the additional incentives. So, where are we? They are people, there are incentives, and there are people’s behaviors.

Enter Trade

One of the common themes among all humans in all societies is the idea of trade. One guy has a fish, and the other guy has a box of crackers. They trade if and only if they each want the other thing more than they want what they have. This is true with kids on the playground trading peanut butter sandwiches for cans of Coke, or guys buying billion dollar submarines.

First Rule Of Trade

We only trade when we want the other thing more than we want the thing we have. If you’ve got five bucks in your pocket, you will only but a peanut butter and bacon burrito (wait, what?) for five bucks if you want the weird burrito more than your five bucks. (Maybe the burrito girl is super gorgeous or something).

Hallucination Time

Now we need to hallucinate some stuff. This is how the supply-demand curves are formed. By imagining things that don’t exist. True story. So, let’s imagine a large football stadium. On the left side, is a bunch of people who are hungry. They each have a varying amounts of money. On the right side, are all sellers of stuff. They all have the same stuff.

For our experiment, we’ll imagine something less gross than a peanut butter and bacon burrito. We’ll imagine a plain old cheeseburger. Let’s imagine they all have their cheeseburger stands all set up on the right side of the field. We need to make a couple of assumptions.

All Buyers Have Different Values and Different Amounts Of Money

Some buyers love cheeseburgers and are rich. Some hate cheeseburgers and are poor. All we know is they are somewhat interested in eating something, and they all have some cash on them.

All Sellers Have Different Values And Different Food Production Skills

We’ll assume that all cheeseburgers are totally uniform. But some of the sellers are super skilled in everything about making cheeseburgers. They’ve got mad connections with bread makers, meat distributors and the cheese people. For others, this is their first day. The reason we make these assumptions is that they all have different inputs. Meaning some of them only spend a buck per cheeseburger on all the raw ingredients. Others spent maybe three or four dollars.

Imagination Time

Let’s imagine we conduct a quick poll of everybody on the left side of the field. The cheeseburger buyers. We first start off by saying, “Hey, how many of you guys would buy a cheeseburger if it were only fifty cents?” And everybody raises their hand. Then we say, “How many of you cheeseburger eating people would buy a burger for a buck?” And less people would raise their hand. Then we keep going, increasing the price every time. By the time we got up to ten bucks, only one guy (maybe a rich guy who loves cheeseburgers) raises his hand.

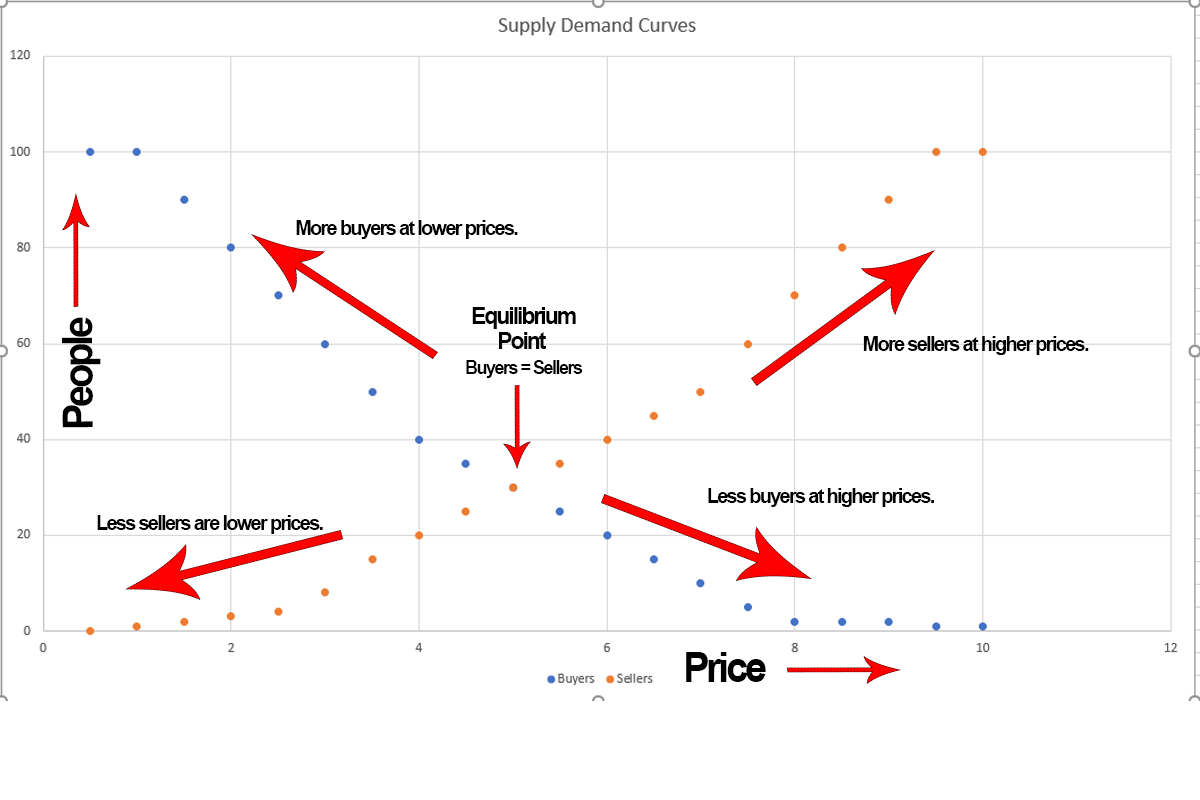

Hypothetical Demand Curve

This set of points represents the demand curve. The amount of people who would buy the cheeseburger at these different hypothetical points. In any group, it makes sense. The maximum people would buy at the cheapest price. The minimum would buy at the maximum price. Nobody, (at least not a rational thinking person) would not buy a burger at a dollar, but would buy a burger at $2. (Unless he’d been hypnotized to think that $2 was less than $1, but I digress).

Seller Questions

We can do the same thing for all the sellers. Only this time, we start at the higher price. “Hey, how many of you cheeseburger selling people would sell a cheeseburger to somebody if they offered you ten bucks?” Everybody would raise their hand. Then we ask about if the price was nine bucks. A few less people would raise their hand. All the way down to fifty cents, where only the most efficient cheeseburger dudes would sell one. Even if they took loss, meaning it cost them a couple bucks to make the cheeseburger, they still might sell it for fifty cents. Maybe they have a chain of cheeseburger stores around the world, and they are so confident in the quality of their burgers, they’re willing to take a loss, hoping the guy would become a lifetime customer.

Hypothetical Supply Curve

This imaginary set of points represents the hypothetical supply curve. The most people would sell a burger at the highest price. The least people would sell a burger at the lowest price. It’s highly unlikely that anybody would not sell a burger for $5, but they would sell one for $4, unless of course the customer was a Jedi or a hypnotist or something.

Where The Rubber Meets The Road

In real life, these two hypothetical lines cross at some point. The place where they cross is where the price is going to be in real life. This is when the most amount of cheeseburgers are sold to the most amount of people. This is easy to imagine. Let’s suppose people from the eating side start wandering over to the buying side. Assuming all the cheeseburgers were identical, the price of a cheeseburger would quickly reach an equilibrium.

Nobody who was selling could sell higher than the equilibrium price. Meaning if the equilibrium price was $5.00, and some guy tried to sell cheeseburgers for $6.00, nobody would buy from him since everybody around him would be selling for $5.00.

Similarly, if everybody who was buying was paying $5.00, no buyer (unless he was a hypnotist) could get a cheeseburger for $2.00, since no seller would sell for $2.00 if everybody else was paying $5.00.

The Happiest Sellers

The happiest sellers would be the ones who were making the most profit. Some of them wouldn’t make any profit. Meaning it would be likely that some of the cheeseburger sellers had spent $4.50 per burger in raw materials. So for each cheeseburger they sold, they’d lose $0.50. The guys who made theirs the cheapest would make the most profit.

The Happiest Buyers

The happiest buyers would be the ones who thought they were getting the best deal. Maybe there were a couple of guys who would have been willing to pay $10 for a burger, and thought getting them at $5.00 a pop was a bargain. On the other hand, maybe there were a few guys who would have bought one had they been $1.50, but not a penny higher. These guys would have gone home empty handed. But that would have been their choice.

Supply And Demand Fluctuations

So far, this is pretty straightforward. If you take a basic econ class, you can watch the professor draw the lines on the board, and nod you head when he makes the points. Next usually comes with supply and demand adjustments, and how they affect the resulting equilibrium. If you are only paying attention to lines on a chart, and trying to remember all this stuff for a midterm, it’s pretty boring.

But when you take the time to consider the human psychology aspect if it, and why these dry economic theories are really descriptions of human action, human thinking, and the human condition, it’s pretty interesting. Let’s look at four different thing that can happen to the price equilibrium (the final price when buyers and sellers start doing business) under four different conditions.

Increase In Supply – Same Demand

This would mean that there are the same number of cheeseburger buyers on the football field, but for some reason a whole bunch of cheeseburger sellers show up. When they first run in and set up their stalls, they have no customers. They look around, see the people buying, and see themselves and all of the other newly added sellers with no customers.

They could choose to do two things. One is to simply wait and hope somebody comes over. The second is what usually happens. All they need to do is lower their price by ten cents, and start screaming that they’ve got the cheapest burgers in the place. Pretty soon another lowers his price, in an effort to attract customers. Maybe he lowers his price by fifteen cents. Then another guy lowers his price by a quarter. This continues until a new price equilibrium is created. End result?

Increase in supply with the same demand creates lower prices.

Decrease in Supply – Same Demand

This ones a bit more difficult to imagine. Instead of a bunch of new cheeseburger sellers coming on the field, half of them pack up and go home. Maybe it’s time to pick their kids up at school or something. Now there are the same people buying cheeseburgers, but there less people selling them.

Let’s do a separate mental experiment. Let’s imagine you nine other people are selling cheeseburgers. You show up every day, and each one of you sell 100 cheeseburgers to 100 people. So a total of 1000 cheeseburgers are sold to 1000 people (10 sellers at 100 sales each). But for some reason, one day you show up and you’re the only seller. But there are 1000 people waiting around to buy cheeseburgers.

Would you sell them for the same price? You could, but something might happen. Meaning all the people who are eager for cheeseburgers, and are expecting to buy them for say, $5 a pop, might not like to go home empty handed. In fact, some of them might offer $6 for a cheeseburger. Some would even rather pay $10 for a cheeseburger, as they’d prefer that to going home empty handed.

When the supply increases, the suppliers will underbid each other. But when the supply decreases, the buyers will outbid each other. Even if they don’t, many sellers will slowly raise their price, since there are so many people. The net result from a decrease in supply with the same demand is:

Decrease in supply with the same demand is an increase in prices.

Increase In Demand With Same Supply

The next two will be pretty simple, since its the flip side of each of what we described above. If the same cheeseburger sellers are sitting there, and a whole flood of cheeseburger lovers come onto the field, the price will go up. More people with less cheeseburgers. Either the sellers will slowly increase the price, or the buyers will start bidding higher.

Now, let’s consider this. Suppose only one cheeseburger seller raises his price from $5 to $6, and none of the other guys raise their prices. Who would buy his $6 cheeseburgers when all the others are $5? Plenty of people. They’d rather pay $6 and not have to wait in line than $5 while waiting in line. When people are waiting in line, they are thinking, “I hope they don’t run out!”

So it’s really not a comparison of a $5 cheeseburger vs. a $6 cheeseburger. It’s a guaranteed, $6 cheeseburger right now, vs. a maybe $5 cheeseburger after waiting in line for twenty minutes.

Increase in demand with same supply ends with a higher price.

Decrease in Demand With Same Supply

Let’s say half of the buyers decide to leave, or don’t even show up. Now you’ve got a lot less buyers, and all of the cheeseburgers sellers would start to worry that they might not sell as many as they’d hoped. So we’ll get the same thing as a decrease in supply with the same demand, a decrease in prices.

Decrease in demand with same supply ends with a decrease in price.

Not Just Lines On A Graph

All of the lines that describe supply and demand, and changes in both are all descriptions of what humans do. They are not expressions of how some professor thinks humans should behave. It’s a description of human behavior. Of what we would expect normal humans would do under certain situations. But this simple idea of supply and demand, and what happens when either side changes, has some pretty far reaching consequences.

The Invisible Hand

Adam Smith coined this term in his book, “Wealth of Nations,” (on Amazon here) which was first published in 1776. What does he mean by the invisible hand? Imagine a massive globally connected economy. Kajillions of products swirling around the world, being used in all kinds of production to make all kinds of products. Think of something like your phone or PC.

These common objects are made with thousands of materials that come from around the world. The various components in your phone are assembled all around the world. The simple idea of supply and demand keeps everything coordinated. Let’s consider something like “rare earth elements.” These go into all kinds of products.

There’s a few countries that mine them, and two of them are China and Australia. Let’s consider a company that uses terbium, a rare earth element in it’s production. Let’s say the current price of terbium is $5000 per 100g. And it stays at that price for a while.

But then the price of terbium starts to inch up. What will this do? The first thing that will happen is that the factories that use the most terbium will start hunting around for a cheaper price. Another thing that will happen is people that mine plenty of rare earth elements will see the price of terbium going up. And they might decide to increase their production, since they can now sell it for more.

Let’s say that there was political instability in China, which is why the price started to go up. The other mine was in Australia. Once the price went up enough, it made sense for the Australians to start mining it. Pretty soon, they had enough of it, and could sell it cheaper than China.

Soon all the factories that use terbium in their production started buying it from Australia. China would notice this and maybe fix their political problems, since it was costing them sales. So they started selling it cheaper.

No Communication Required

Nobody in the factory needed to talk to anybody in China or Australia. None of the guys in the Australian mine needed to talk to the guys in the Chinese mine. The only thing anybody needed to know was the price of terbium. This information, and this information only, was the only thing needed to keep the terbium flowing around the world.

Signals To Producers

Any increase in price in any raw material is a signal to all the producers, or potential producers of the raw material. The price going up means that whoever wants to can produce some and sell it at that price. Maybe it doesn’t make sense to one particular producer to make it if they can only sell it for $500 a gram. But if it sells for $550 a gram, they can make a profit, so they start to make it.

Signals To Users

If any one raw material starts to go up in price, it sends a clear signal to all the people who use that material: You’d better start looking around for another supplier. If it goes up too much, then their R and D departments might start coming up with designs that don’t require terbium.

Simple Ideas – Worldwide Ramifications

The simple human behavior around supply and demand, and changes in both sides, keep the massive global economy all in a seemingly magical balancing act. It can even serve to protect natural resources. If any raw material becomes very scarce, it will also become very expensive. That means it will become too expensive for anybody to use.

Goods Go Where They Are Wanted Most

If there is one guy in some small island in the middle of nowhere that produces something the entire world wants, where does he decide to send it? Whoever is willing to pay the most. If somebody is willing to pay him $100 a gram for whatever it is, then that person gets it. He doesn’t need to know what he’s going to use it for, or even what language the other guy speaks.

Increasing Prices Encourage Alternative Sources

If something starts going up too high in price, people naturally start looking for other ways to satisfy their needs. For example, if there was some worldwide cow disease that killed most of the cattle, cheeseburger prices would go through the roof. But anybody who buys beef would see the price, and be able to choose something else, like pork or chicken or fish.

Communication Of The Hive Mind

In a sense, this simple supply-demand idea, and the worldwide pricing system of everything is essentially the communication system of the hive mind. It’s a very simple and very effective technique, that requires little human input, that the hive mind uses to figures out how to take stuff out the ground in Africa, ship it to Australia, use it to build stuff and then ship those finished products to Asia.

It’s really not that different from a single body. We eat stuff (raw materials) and our body just “knows” which parts of our body needs fuel. The worldwide brain is the same way. It just “knows” where to produce raw materials, and where to send them. Very little human communication or oversight is needed.

It’s mind boggling to think of the many similarities in this global hive mind that humans have created over the past few hundred years, and our own individual mind body systems.

Learn More

Mind Persuasion has plenty of books and courses designed to help you maximize your own mind body system to get the maximum results for your efforts.

Mind Persuasion Books

Mind Persuasion Courses